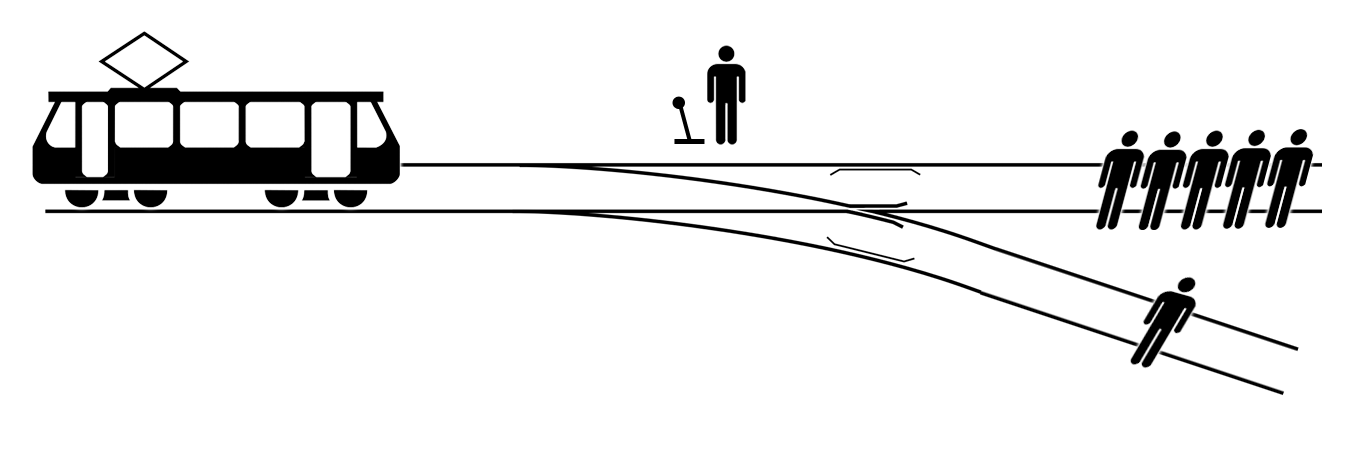

Figure 1: The classical trolley problem: the actor can pull the lever to save five people on the upper track from the out-of-control tram, condemning the person on the lower track to die. Image CC BY-SA 4.0 McGeddon @ Wikipedia

In the recently published “Trolled by the Trolley Problem”[1] Alexander G. Mirnig and Alexander Meschtscherjakov point out the severe limitations of the trolley problem with regard to ethics- and technology assessment as applied to (semi-)autonomous vehicles. They go on to criticize the amount of effort spent on it and argue for better foci. In this essay, I'll give a short overview over their critique and want to point out other, wider potential issues in need of studying and societal deliberation beyond the artificial, construed confines of the trolley problem.

Limitations of the Trolley Problem

As laid out by Mirnig and Meschtscherjakov, the trolley problem (see fig. 1) is intended to make a point regarding ethics theory and specifically designed to be unsolvable. Deontological, i.e. rule-based, ethics-frameworks usually hold a rule that forbids killing another human being. The trolley-problem presents a situation where breaking that rule seems to align better with one's moral sense, thus making an argument for consequentialist utilitarian (i.e. outcome-focused and value-function based) ethics, where lives are compared numerically. It was never intended as a benchmark to be applied to the design of artificial moral agents, as in the case of autonomous vehicles.

In particular, Mirning and Meschtscherjakov argue, that the vast majority of situations encountered on the road are epistemological dilemmas, i.e. where the problem lies in incomplete knowledge and given more knowledge the dilemmas could be resolved. As such they argue that an improvement of sensor-technology and inter-vehicle-communication in itself helps autonomous vehicles to act more ethically, e.g. preventing crashes like the one in Williston, Florida, where a Tesla Model S failed to detect a white tractor-trailer against the sky [2].

Even where only actual ontological dilemma-situations are considered, i.e. ones wherein all knowledge is available but the situation still presents itself as a moral dilemma, trolley-problems have several inherent flaws and in general don't represent day-to-day road situations at all. Regarding the inherent flaws, usual ethic-theoretical arguments against trolley problems are, e.g. that they conflict with deontic consistency, i.e. that situations can't both mandate and forbid some action at the same time. Another argument is, that even from a deontological/rule-based perspective the options are not symmetrical and one of the options represents more rule-violations or a more severe one. For situations that truly were symmetrical, the choice wouldn't matter.

But the most striking critique, in my opinion, is that the trolley problem is stated without context, without a description of how this situation came about. Taking it into account allows studying these situations from an intentionalist perspective. In this perspective, an agent with the intention to save lives would be ethical. But even from a consequentialist (i.e. outcome-oriented) perspective, this added context allows “solving” the dilemma but placing the burden with the agent responsible for bringing about the situation in the first place. This puts the focus on avoiding trolley-problem-like situations (by improving sensors, communication and decision-making algorithms through transparency, scrutiny, and review).

Regarding this shift of focus to the situations preceding trolley-problem-situations, Mirning and Meschtscherjakov argue that in front of court a human driver would be interviewed whether they were intoxicated or not, if they had a valid driving license and how the situation came about, not what the exact split-second decision-process was in the last moment before the crash. Thus, they continue, the same measure should apply to artificial agents. Media coverage [2, 3] and public outcry following the first fatalities [4] involving (semi-)automated cars, raise doubt that this will happen, however. Even though a common hope is that self-driving cars will have a lower accident rate than human-driven ones, these first fatalities and the surrounding discussion might and assign autonomous vehicles a symbolic meaning of “calculating killer cars”. In this sense, Mirnig and Meschtscherjakov point out that “trolley dilemmas highlight a potential authority of machines over human life that society is uncomfortable with.

Whose Ethics

What the trolley problem is helpful for, however, is pointing out that there are no universal moral principles to be followed. In the same vein, one might argue, that there's no universal, utilitarian value-function. The famous “Moral Machine Experiment”[5] highlights this and amongst others shows how people with different cultural backgrounds would decide in auto-generated, wild variations of the trolley problem (e.g. “two men and one female athlete versus two large men and one large woman”). For instance, people from countries in the “Southern” group (assigned according to the Inglehart–Welzel Cultural Map 2010–2014[6]) chose the lives of higher-status persons, women and children more often (compared to other factors) than people from countries in the “Western” group.

This debunking of any notions of universalism and moral realism opens a discussion of whose ethics a (semi-)autonomous car should follow and which moral design decisions were made by those who construct it.

For instance, one might argue, that the human driver is the ultimate moral authority in (semi-)autonomous driving and legally fully responsible. For one this would require having some sort of system, that gets initialized with the human agent's personal utility function, or moral codes or virtue system whenever they get into the car. This would also require making these entirely encodable or risk introducing bias through what the system can internally represent and what it can't. Also, especially in semi-autonomous but to a lesser degree also in autonomous vehicles, the decision-making process needs to be transparent to the driver/user of the vehicle, if they're the ones to hold the responsibility.

Bias

Assuming that this process of customization will not exist or will be less than total, we can argue that more or less hidden biases will exist in this technology. Most of it is developed primarily in and for the “western” nations – of the recent KPMG Autonomous Vehicle Readiness Index report [7, 8] 7 of the first 10 and 13 of the first 20 nations were counted to the “Western” group by the authors of “The Moral Machine experiment[5]. As “code is law” [9] the moral frameworks and laws of these technology-driving nations is imposed on other cultures, with potentially radically different frameworks. This makes the technology less useful for already economically disadvantaged nations (e.g. the “Global South”) and directly threatens to supplant their moral codes, virtues, and values in this context. Especially given the historic relationship of colonialism and (neo-)imperialism this seems particularly objectable. An example from a different type of algorithmic system would be how social media censors of US-owned social networks censor according to US-American values (e.g. “hate speech is free speech” but too much skin or anything related to menstruation is reprehensible) instead of local ones.

Figure 2: Google's self-driving car (CC-BY-NC-SA Willy Volk @ flickr)

Regarding the basic usefulness, biases might also and especially come in the form of which environments autonomous vehicles are tested in and thus will perform well. Currently, fully autonomous cars seem to be mostly tested in Silicon Valley (and similar regions) on traffic-light roads (e.g. fig. 2) and thus will very likely struggle in areas without roads or traffic that looks and acts substantially different (e.g. fig. 3), as previously unknown problems arise and hidden assumptions rear their head. To counteract these biases, as with other algorithmic systems, diverse teams and an inclusive design and testing process are necessary, as well as transparency of algorithms, to allow for external scrutiny. Additionally, very likely legislation and institutionalized accident assessment will be necessary to regulate in the interests of the people, as self-regulation of algorithm-producing corporations has shown to be ineffective as e.g. shown by repeated scandals around Facebook and in particular Uber, that builds its business model on exploiting legal loop-holes or straight-out breaking the law [10].

Figure 3: Traffic in Vietnam (CC-BY-NC-ND Eric Havir @ flickr)

Fairness

Beyond purely algorithm-related issues, there are several other issues surrounding self-driving cars, that will need addressing, for them to be at least not detrimental to the broader public and humanity as a whole and ideally beneficial.

For one, driving is one of the most common occupations. In the US, as 2014 census data shows, an average of 3% of the over 16-year olds (i.e. 4.4 million persons) are working as drivers[11]. For some regions this statistic is even higher, going up to 9%. The most common among these occupations is truck driving, a field where the push to automation is strong, with the first step being platooning systems that link trucks driving behind each other together, with only the lead truck being controlled by a human. These jobs will be lost, and very likely not many of the affected persons will find employment in the new, more engineering-oriented and academic occupations surrounding these systems. Also, in the run-up to full-automation ever-increasing work-place surveillance is being forced on these drivers [12].

As another socio-economic factor, most self-driving cars are massively expensive at the moment (e.g. the Tesla cars). Even if this wealth-caused access-gap closes eventually, adoption will start with wealthier persons. Any changes made to the public environments will further disadvantage already marginalized persons. E.g. some realization concepts for a widespread adoption suggest lanes reserved for self-driving cars to reduce risks of accidents when interacting with human-driven vehicles. Introducing this and other concepts primarily benefit those who can afford and chose to own autonomous cars at the disadvantage of everybody else. This wouldn't be a new trend/relation, however, as the same holds for human-driven cars towards everyone else, given societies prioritization of car traffic in the last century, that is only slowly being reversed in some places. People who can't afford or chose not drive cars feel the full effect of the pollution caused by them and lose (traffic) space, that could be used for public transport, bike lanes, pedestrian zones, parks, etc. Especially in rural areas where public transport is continuously reduced in favor of roads for car traffic, not being able to afford one makes one's life severely harder. Depending on how we as a society decide to use the self-driving car technology it might further strengthen these effects or help alleviate the problems by e.g. being available as a cheap, on-demand public transport and/or car-sharing system, that gives people mobility who couldn't drive a non-autonomous car (e.g. due to age, disabilities, etc).

Summary

Summarizing, it can be said that despite the trolley problem's prominence it is badly suited for ethics discussions surrounding self-driving cars and generally a bad benchmark for those algorithms’ performance. It highlights, however, a need for algorithmic transparency and increased facilities to prevent situations such as these from coming about in practice. Additionally, in its original purpose points out that there is no such thing as a universal moral system, raising the question of whose moral judgment the vehicles will follow. In this sense, looking beyond the trolley problem, a plethora of issues of and around self-driving cars present themselves, that require addressing for this new technology to be widely beneficial. These include issues of “West”-centrism, (algorithmic) bias, potentially deepening socio-economic divides, as well as a threat to a large number of people's jobs and thus livelihood. By deliberating how we as a society want to engineer, regulate and most of all use this new technology, it bears a promise of great benefit for all but also, great harm for (already) marginalized people.

References

[1] A. G. Mirnig and A. Meschtscherjakov, “Trolled by the Trolley Problem: On What Matters for Ethical Decision Making in Automated Vehicles,” in Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI ’19, 2019, pp. 1–10.

[2] D. Yadron and D. Tynan, “Tesla driver dies in first fatal crash while using autopilot mode,” The Guardian, 30-Jun-2016.

[3] S. Levin and J. C. Wong, “Self-driving Uber kills Arizona woman in first fatal crash involving pedestrian,” The Guardian, 19-Mar-2018.

[4] “List of self-driving car fatalities,” Wikipedia. 05-Jun-2019.

[5] E. Awad, S. Dsouza, R. Kim, J. Schulz, J. Henrich, A. Shariff, J.-F. Bonnefon, and I. Rahwan, “The Moral Machine experiment,” Nature, vol. 563, no. 7729, p. 59, Nov. 2018.

[6] R. Inglehart and C. Welzel, Modernization, cultural change, and democracy: The human development sequence. Cambridge University Press, 2005.

[7] R. Threlfall, “Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index,” p. 60, 2018.

[8] N. McCarthy, “The Countries Best Prepared For Autonomous Vehicles [Infographic],” Forbes. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2018/10/23/the-countries-best-prepared-for-autonomous-vehicles-infographic/. [Accessed: 12-Jul-2019].

[9] L. Lessig, “Code is law,” The Industry Standard, vol. 18, 1999.

[10] T. B. Lee, “Uber has a secret program to foil law enforcement,” Vox, 03-Mar-2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.vox.com/new-money/2017/3/3/14807820/uber-secret-program-city. [Accessed: 12-Jul-2019].

[11] M. Fahey, “Driverless cars will kill the most jobs in select US states,” 02-Sep-2016. [Online]. Available: https://www.cnbc.com/2016/09/02/driverless-cars-will-kill-the-most-jobs-in-select-us-states.html. [Accessed: 12-Jul-2019].

[12] Vox, “How job surveillance is changing trucking in America,” 20-Nov-2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G_UHknhNbAQ. [Accessed: 12-Jul-2019].