This text is the last portfolio-submission for the course “187.329 - VU Sociology of Technology” ) and deals with the the questions listed below. It's mainly based on pages 74-88 and 188-195 of W. Sachs’ “For Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires” (translated by D. Reneau, 1992) and studies the structuring function and symbolic meaning assigned to cars.

The questions:

3.1: What did the implementation of automobile traffic mean for the distribution of space and power in public spaces of mobility and for the humans’ collective social living? Explain and give examples.

3.2: In what way and why did traffic education and road safety training become requirements for the use of public spaces of mobility for ALL traffic participants (and not only for car drivers) in the wake of the implementation of automobile traffic?

3.3a: Use 3 concrete examples from Austria (may it be Vienna, another city or rural areas, …) to elaborately explain (in terms of a thick description and analysis) the street-oriented transformation of the humans’ living environment since the 1960s discussed by Sachs.

3.3b: Does this process still last today; or is it declining; or does it last while trends in the other directionare observable as well; or …?

Other posts from the same lecture can be found here.

Task 3.1

What did the implementation of automobile traffic mean for the distribution of space and power in public spaces of mobility and for the humans’ collective social living? Explain and give examples.

The wide-spread adoption of the automobile and the linked political prioritization of car traffic and corresponding reshaping of our living environment widened existing power gaps. Benefits for those behind the wheel were bought at the expense of everybody else, as Sachs discusses extensively in “For the Love of the Automobile” (p. 188ff; orig. 1984, engl. 1992). While it is true, that car ownership is no longer a privilege of the richer classes as it was at the beginning of the 20th century, cars are still more likely to be owned by men aged 25-60 than children, women or the elderly, i.e. people who with less access to disposable income. Comparatively recently, Statistik Austria published data on the mobility of private households (“Mobilität Der Privaten Haushalte 2014/15” n.d.). 23% of households in Austria didn't own cars in 2014/15 and roughly two thirds of those who did only owned one car, even at an average household-size of 2.23 people. Note, that no exact data could be publicly found that shows the average size of just the 1-car-households.

Regarding the direct manifestations prioritization of car traffic: roads can be considered better for vehicles, if they're straight and without obstacles/slow-downs to enable high speed, multi-laned to enable a high traffic volume, if they go everywhere in the country thus providing accessibility and penetrability, and if they hold very limited surprises thus increasing safety at high speeds. Thus, they're very much what our highways look like. In contrast, as Sachs points out, pedestrians and in particular strollers prefer clean air, a non-noisy environment, winding roads with nooks and crannies and many surprises to discover and study, i.e. a scenery that changes at the pace of a pedestrian, not a speeding car, as evidenced by remaining cores of medieval cities, e.g. Vienna's first district. In fact, the very presence of pedestrians themselves, even on roads they could freely walk at the turn to the 20th century, has been deemed risky by drivers and automobile-interest-groups, that have pushed for strict limitation on where they can walk. More on that in Task 3.2. These limitations also found reification in structural measures. Pedestrian and cyclists were pushed to boardwalks and bike-lanes and where possible physically separated even more, e.g. via walls and crossings realized as foot-bridges or foot-tunnels.

All of these measures took considerable amounts of space away from non-drivers and dedicated and exclusive the to car-traffic, a fact most keenly felt when one participates in a Critical Mass or one of the Viennese Friday Night Skates and feels somewhat like an alien in a car-world while crossing a highway-bridge, passing underneath huge overhead-signs.

As portrait by Sachs in “For the Love of the Automobile”, the ‘mobilization of society’ came hand in hand in general with a view of “space as a distance to overcome” and in particular with a hierarchisation of places. The goal of road-construction has been to optimize traffic between the places deemed important by the decision-makers, even at the cost of those places in-between. For the urban this meant e.g. sacrificing beer gardens and parks. In the countryside this meant e.g. flattening residential areas and forests. Additionally, as Sachs describes it, for both urban and rural areas it leads to a desolation of villages and inner cities as businesses move to the edge of town, closer the on-ramp or entirely away from the area. Especially for people from suburbs and towns, long commutes using the car have become the norm. Losing or not having access to one there prevents participation in society and in many cases strains or threatens peoples livelihood (e.g. by not being able to work, or by weighing a visit to the doctor against a long commute with public transport). In Austria this hits the 13% of households without a car in small towns (<10,000 inhabitants; data from “Mobilität Der Privaten Haushalte 2014/15” n.d.).

Lastly, man-made climate change caused to a very significant degree by car-traffic, has vast and serious effects on collective social living and tends to hit less privileged people worse, thus deepening existing power-imbalances. However, this topic is beyond the scope of this assignment and it's primary source.

Task 3.2

In what way and why did traffic education and road safety training become requirements for the use of public spaces of mobility for ALL traffic participants (and not only for car drivers) in the wake of the implementation of automobile traffic?

As mentioned in the section above, the prioritization of car-traffic meant that significant portions of space were dedicated to car traffic. Stromberg writes in “The Forgotten History of How Automakers Invented the Crime of ‘Jaywalking.’ (11/2015, vox.com) in the early the responsibility and liability of avoiding accidents lay with the stronger and faster traffic participant, i.e. the persons behind the steering-wheels of cars. High rates of injuries and fatalities, quite disproportionately affected pedestrians, especially children, women and elderly. This leads to petition in 1923 in Cincinnati to mechanically limit cars speed, which failed. As a push-back automobile-interest-groups began a successful series of campaigns to establish the concept of jaywalking and outlaw it, thus forcing pedestrians of the streets. A key-point was to shift the blame for accidents towards the run-over pedestrians.

This matches with Sachs’ accounts of west-Germany in 1980 regarding the injury-rates and the article from the Berliner Tageblatt of July 4, 1928 he cites on page 191, about the coming regulations, that also calls consideration of traffic and caution when crossing, forbids bicycling during the day, and forbids people to walk more than “three abreast” on the side-walk.

Given this shift of liability (and sheer want for personal safety in the “Tin Avalanche”) require pedestrians and cyclists to learn them, to participate in car-dominated public spaces.

Task 3.3a

Use 3 concrete examples from Austria (may it be Vienna, another city or rural areas, …) to elaborately explain (in terms of a thick description and analysis) the street-oriented transformation of the humans’ living environment since the 1960s discussed by Sachs.

Praterstern

Around 1900:

Screenshot off of Google Maps taken on May 27, 2019:

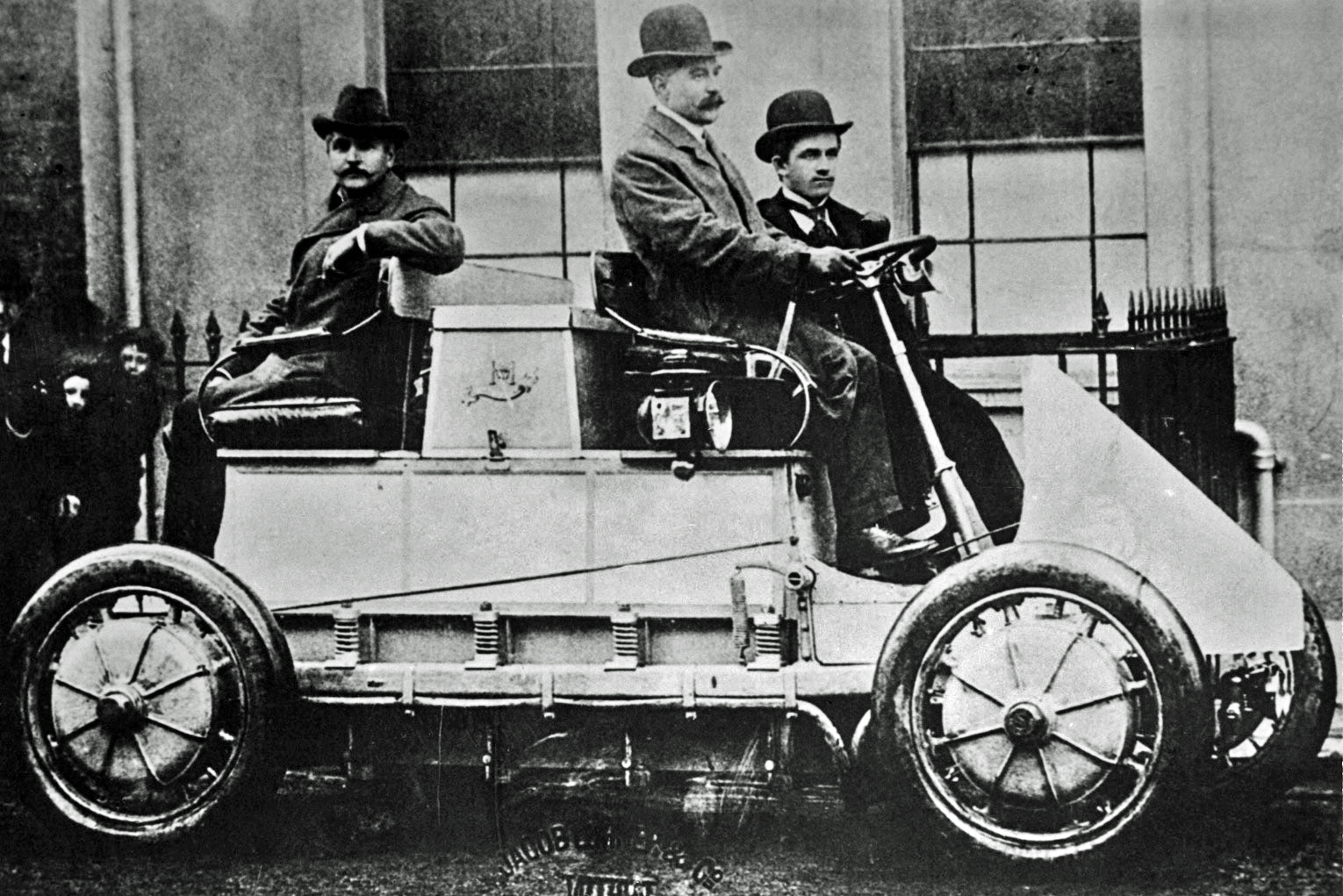

As can be seen in the figures above in the early 20th century pedestrians, riders, coaches, wagons and trams co-existed. In 2019 the area is a huge round-about, with only limited opportunities for crossing, if one doesn't want to risk getting hit by traffic, especially around rush-hour. Most prominently this also directly affects the short walk from the subway-station to the amusement park that large number of people take every day.

Wildon

This is the small town in southern Styria my grandparents have lived in. As evidenced by the old town-center, there used to be a handful of small shops and craftspeople there, that covered everything needed for living. Nowadays the only possibility for groceries is an hour walk away, across a major through-street, making it hard for people without a car and difficulties when walking to do the daily necessities.

Task 3.3b

Does this process still last today; or is it declining; or does it last while trends in the other directionare observable as well; or …? Substantiate and argue for your answer/analysis!

A lot of movements and cities are purposefully reclaiming public space for non-cars. On the one hand there's movements like Critical Mass that purposefully take back the streets. On the other there're districts and entire cities disincentivizing car traffic, by reducing the number of thru-streets, e.g. as has happened in Neubau in the last years, experimenting with shared spaces.

In contrast, however, there's still extensive highway-constructions going on to widen streets, dig new tunnels, etcetera, that most definitely come with both high financial as well as social and environmental costs for those affected. Especially in the latter regard, we all pay the price for car-traffic that is constantly increasing globally, especially given the threshold countries increasing (catch-up) mobilization.

References

- “Mobilität Der Privaten Haushalte 2014/15.” 2016. October 20, 2016. https://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/menschen_und_gesellschaft/soziales/ausstattung_privater_haushalte/110362.html.

- Stromberg, Joseph. 2015. “The Forgotten History of How Automakers Invented the Crime of ‘Jaywalking.’” November 4, 2015. https://www.vox.com/2015/1/15/7551873/jaywalking-history.

- Sachs, Wolfgang. 1992. For Love of the Automobile: Looking Back into the History of Our Desires. Univ of California Press.